This article appears in the December 2020 issue of Front Vision, an educational Chinese-language magazine for kids. It is reproduced here with permission. Read about my other recent articles for Front Vision here.

The Greening of the City

by Kathryn Hulick

Wild nature seems to be the opposite of a human city. In nature, curvy and messy lines dominate, while in a city, most lines are straight and neat. In nature, the weather changes from rain to heat to cold, while in a city, roofs and heating and cooling systems keep people comfortable. In nature, growth happens chaotically, while in a city, growth is planned and controlled. In a city, people often pave over nature or fence it in. They tame it to the point that it may be hard to notice. But nature is always there. In fact, it is essential.

In a city, green space provides a huge range of benefits. Let’s say you build a new city park in a vacant lot. As people visit the park or exercise there, their moods and health will improve. “One of the problems that many people around the world in cities face is that they don’t get enough physical activity,” says Jennifer Wolch, an expert in city planning at the University of California, Berkeley. Parks and other green spaces help promote healthy activity, especially if recreational programs and events such as baseball games, hikes, or dance classes happen there.

The land bordering the park will increase in value because most people prefer to live or work near a natural space. The park will improve air quality and even help combat global warming because plants absorb pollutants and carbon dioxide. Plants and bodies of water also absorb heat, lowering the temperature on hot days. And, of course, trees provide shade. So heat waves will be less dangerous for people in and around the park and

buildings nearby will use less energy for cooling. Floods will also be less likely around the park. That’s because when it rains, water will sink down into the soil instead of draining into pipes that may overflow.

Parks, Gardens, and Yards

People have realized that green spaces are important to the success of a city and the happiness of its inhabitants for over a hundred years. Back in 1898, Ebenezer Howard, a town planner in England, came up with a concept for a “garden city.” It was designed as rings of concentric circles. The innermost circle was a garden surrounded by public buildings. Circles for housing also contained parks and gardens. A railway surrounded the outermost buildings, and the land beyond the railway was reserved for farming and wild forests. The city wouldn’t be allowed to expand into this green space. “Human society and the beauty of nature are meant to be enjoyed together,” he wrote. The city of Letchworth in the UK was built in the early 1900s according to his plan.

Howard came up with his idea in response to the industrial age, which had overwhelmed many cities with huge populations, smoke, and pollution. The trend of building suburbs around cities can also be traced back to his ideas. In a suburb, most people have large yards and parks are nearby, but residents can still access the city. In traditional cities and suburbs, nature gets sectioned off into particular places, such as parks, gardens, or yards. Even trees lining the streets may be fenced in. Nature is there, but it’s kept separate, something to look at on the way by or visit on your day off.

However, setting aside large amounts of space for parks and yards means not building other things—like affordable housing, schools, roads, or other important structures. But the planned city park or private yard is not the only way to bring nature into a city. Around the world, city planners and architects have found creative ways to work with the space they have available. In the 1940s, Seoul, Korea, paved over the top of the polluted Cheonggyecheon, a stream. A few decades later, the city built a raised highway over the top of the covered stream. By the 2000s, though, the city had realized it had made a mistake. The government tore down the highway— replacing it with improved roads and public transportation—and uncovered the stream. Now, the area is a popular park filled with greenery.

In New York City, the High Line railway once carried passengers and goods up above the main streets of the city. But as highways replaced railways, the trains stopped running. In 1999, developers planned to tear down the structure. But local people and the city government worked together to instead turn it into a popular walking path. It’s lined with trees and grasses, many of which began growing there when the railway was abandoned.

Many other cities and towns have also converted abandoned railways into trails. Abandoned lots can become community gardens. Alleyways can become green walkways.

These types of projects make a city more beautiful and provide all the benefits of green space discussed earlier, from improving public health to cleaning the air. However, these improvements are usually very expensive. They also make nearby housing and office space cost more. Typically, only very wealthy people can afford to live near a city’s biggest and best natural spaces. When a new park or waterway is developed in a low income community, the residents may not get to benefit. As rents and property taxes go up, they may be forced to move. This is called green gentrification. It happened around the High Line and around the Cheonggyecheon too. Green gentrification is especially problematic in cities where housing is hard to find or expensive, says Wolch. Involving the local community in the planning can help. So can building smaller, less flashy green spaces that aren’t as likely to drive up property values.

Nature, Nature, Everywhere

For centuries, most urban planners have partitioned out parks as separate from living, working, or transportation spaces. Even when builders have thought more creatively about green or blue space (bodies of water like the sea or river), the main goal has usually been to increase the proportion of natural space in a city as much as possible. In fact, the World Cities Culture Forum has ranked the world’s largest cities based on how much public green space they contain as a percentage of total land. Singapore has almost 50 percent green space, while Paris has just under 10 percent. However, thinking about proportion is only the beginning. In reality, the city is not separate from the natural ecosystem—it’s part of it. The city and nature must intertwine.

With this idea in mind, city planners and architects are reimagining how nature fits into a city. “The notion of green space is actively changing and needed to change.” says Wolch. Green and blue spaces don’t have to be separate, fenced-off parks or paths, they can contribute to the functioning of the city. And the city can give back to nature, making sure that local wildlife and ecosystems can flourish. Two examples of this change in thinking are the rain garden and the green roof, both use space in a way that benefits the city as well as the natural environment.

Rain gardens help a city handle excess water. In most cities, a system of stormwater drains, pipes, and ditches carries water away from buildings and roads. As water flows along these channels, though, it gets polluted with dirt, chemicals, oil, garbage, and more. A rain garden does a much better job of handling water. It can be planted anywhere that water tends to flow when it rains, for example, in the median of a roadway or along the edge of a building. The soil of a rain garden contains sand and other materials that help it absorb lots of water whenever it rains. Plant roots remove pollutants from the water before it enters the local water supply.

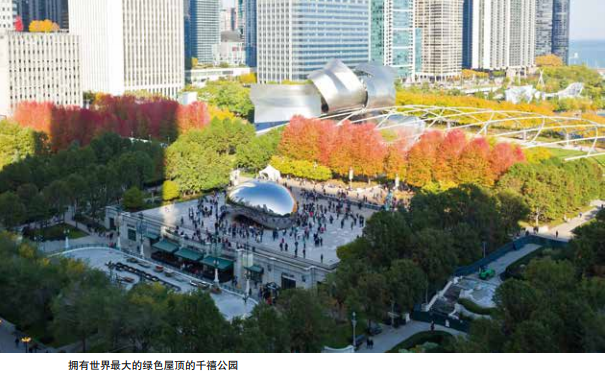

A green roof also helps absorb and filter rainwater. Builders use a special growing medium that will remain loose and a layer of drainage material to help water filter through. Several more layers of material protect the regular roof from water, heat, and the extra weight of the green roof. The simplest green roofs are home to native, hardy plants that don’t require any maintenance or watering.

More elaborate green roofs allow people to walk around through the greenery high above the city. The largest green roof in the world is Millennium Park in Chicago. It’s big enough to host 11,000 people at an outdoor event. Copenhagen, Córdoba, Denver, and several other cities around the world have passed laws that make green roofs a requirement for certain types of buildings. Both rain gardens and green roofs help cool and clean the air, handle excess water, and provide homes for birds, insects, and other wildlife.

A similar structure, called a green wall or vertical garden, provides many of these same benefits. Instead of growing flat on the ground or on a rooftop, the plants in a green wall grow up along the side of a building.

The Symbiotic City

Green roofs, green walls, and rain gardens are all at the heart of a new kind of city: a symbiotic city. Here, nature and the city are impossible to separate. Residents of a symbiotic city recognize that humans and their systems are embedded in nature and natural systems. The closer the two can work together, the more everyone will benefit.

A perfectly neat park with manicured lawns and flower bushes takes a lot of effort to main tain, It needs regular watering, fertilizing, and pesticide. Caretakers must mow the lawn and remove dead plants. On the other hand, a park that is left mostly as natural landscape doesn’t produce waste and requires very little maintenance. The wild, native plants that grow there can take care of themselves. Augustus F. Hawkins Natural Park is in the middle of the city but looks exactly like the surrounding countryside, complete with cacti, sagebrush, and a pond. “It’s one of my all-time favorite parks,” says Wolch. She calls it a gateway to the natural environment.

Augustus F. Hawkins Natural Park and other natural green spaces make room for native plants and animals. Conserving nature and enhancing biodiversity should be goals not only in the forests, oceans, and mountains but in cities too. Unfortunately, in most cities, green and blue spaces are like islands sitting in the midst of a concrete and asphalt ocean. Animals may not be able to find their way to or from these spots. So some cities are starting to think of creative ways to connect green spaces together in order to accommodate local wildlife. For example, populations of bees and other pollinators around the world have been dropping for years. Bees are extremely important to the health of the planet because they pollinate plants. Without bees, many plants would not flower or bear fruit. In response, the city of Oslo in Norway designed a bee highway. It is a route of gardens and green roofs planted with bee-friendly flowers or equipped with bee houses that traverses the city. The city of Los Angeles is planning to build the world’s largest wildlife bridge. It will allow mountain lions and other wildlife to safely cross over a ten-lane highway that currently divides their natural habitat.

A symbiotic city accommodates local ecosystems. Beyond that, it reduces the impact on the natural environment by making its systems more efficient. In a typical city, resources go in and waste comes out. A symbiotic city turns this line into a circle. Things previously tossed out as waste get repurposed and recycled in new ways. For example, in Rotterdam, factories produce a lot of extra heat that used to spew out into the environment. But in 2012, the city began harvesting that heat and feeding it into nearby buildings, reducing the amount of new heat that needed to be produced.

Similarly, trash can be burned for energy, human waste can be converted into fertilizer, and wastewater can help keep parks and gardens of all kinds growing. The Parkroyal hotel in Singapore is wrapped with green walls and sky gardens. To keep those plants thriving, rainwater that falls on the roof gets captured in a tank and then pumped to the gardens. Solar panels provide all the energy needed to run the system. Turning outputs into inputs makes city processes much more efficient on both ends. The city uses up fewer resources and spews out less trash and pollution and fewer greenhouse gases.

New technologies, including sensor systems, artificial intelligence, and cloud computing, help make symbiotic urban systems possible. When the parts of a city can communicate in real time, it’s much easier for those parts to work together.

To keep our planet thriving, cities of the future must become more sustainable and symbiotic. If people keep using up resources and producing waste at the current rate, we will face a number of disasters, ranging from fuel and food shortages to extreme weather due to climate change. Adding green space to cities is important. But we must think beyond parks and gardens toward more creative solutions.